Epilepsy is a common condition that affects the brain and causes frequent seizures.

Seizures are bursts of electrical activity in the brain that temporarily affect how it works. They can cause a wide range of symptoms.

Epilepsy can start at any age, but usually starts either in childhood or in people over 60. It’s often lifelong, but can sometimes get slowly better over time.

Seizures can affect people in different ways, depending on which part of the brain is involved.

Possible symptoms include:

- uncontrollable jerking and shaking – called a “fit”

- losing awareness and staring blankly into space

- becoming stiff

- strange sensations – such as a “rising” feeling in the tummy, unusual smells or tastes, and a tingling feeling in your arms or legs

- collapsing

Sometimes you might pass out and not remember what happened.

Read more about the symptoms of epilepsy.

When to get medical help

See your doctor if you think you might have had a seizure for the first time.

This doesn’t mean you have epilepsy, as a seizure can have several causes and sometimes they’re just a one-off, but you should see a doctor to find out why it happened.

Read about the tests for epilepsy you might have.

Call the emergency serivces for an ambulance if someone:

- is having a seizure for the first time

- has a seizure that lasts more than five minutes

- has lots of seizures in a row

- has breathing problems or has seriously injured themselves

Read about what to do if someone has a seizure.

Treatments for epilepsy

Treatment can help most people with epilepsy have fewer seizures or stop having seizures completely.

Treatments include:

- medicines called anti-epileptic drugs – these are the main treatment

- surgery to remove a small part of the brain that’s causing the seizures

- a procedure to put a small electrical device inside the body that can help control seizures

- a special diet (ketogenic diet) that can help control seizures

Some people need treatment for life. But you might be able to stop treatment if your seizures disappear over time.

Read more about treatments for epilepsy.

Living with epilepsy

Epilepsy is usually a lifelong condition, but most people with it are able to have normal lives if their seizures are well controlled.

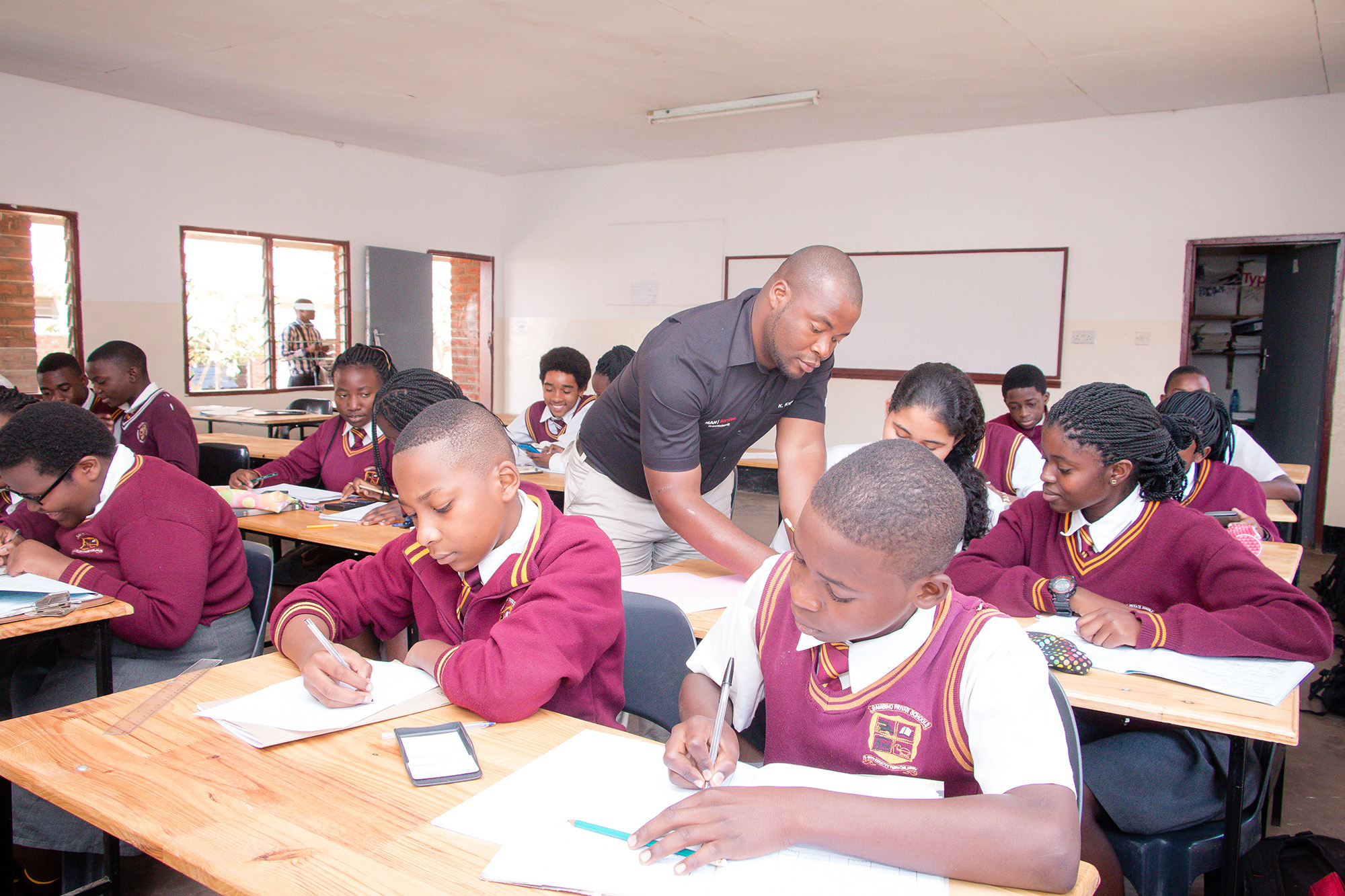

Most children with epilepsy are able to go to a mainstream school, take part in most activities and sports, and get a job when they’re older.

But you may have to think about your epilepsy before you do things such as driving, certain jobs, swimming, using contraception and planning a pregnancy.

Advice is available from your doctor or support groups to help you adjust to life with epilepsy.

Read more about living with epilepsy.

Causes of epilepsy

In epilepsy, the electrical signals in the brain become scrambled and there are sometimes sudden bursts of electrical activity. This is what causes seizures.

In most cases, it’s not clear why this happens. It’s possible it could be partly caused by your genes affecting how your brain works, as around one in three people with epilepsy have a family member with it.

Occasionally, epilepsy can be caused by damage to the brain, such as damage from:

- a stroke

- a brain tumour

- a severe head injury

- drug abuse or alcohol misuse

- a brain infection

- a lack of oxygen during birth